-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Foxy 106.9

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Dr. Candice Carter-Oliver Interview

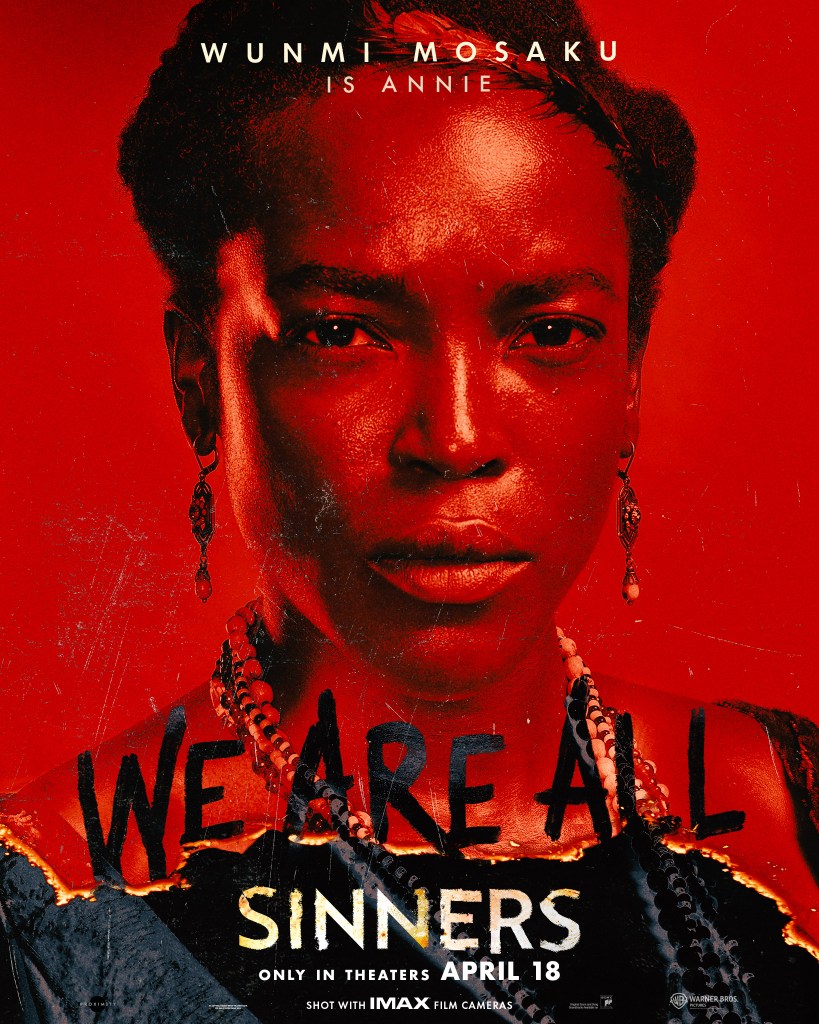

Annie Steals The Spotlight And Holds Our Deepest Infatuation In ‘Sinners’

In Sinners, filmmaker Ryan Coogler and actress Wunmi Mosaku push back against the stereotypes Black women have endured within and outside of our community for centuries. Set in Mississippi in 1932, the southern horror gothic follows twin brothers Smoke and Stack Moore (both portrayed by Michael B. Jordan). The World War I veterans return home after a seven-year hiatus and a run with Chicago’s most notorious gangster, Al Capone. Though the brothers blow into town intent on setting up a juke joint and carving out a legitimate business, the past, the universe, and fate command something different.

As much as the narrative centers on identity, redemption, and dualities, Sinners is also about love. Annie (beautifully portrayed by Mosaku), a Hoodoo conjurer, spiritual leader, and healer, is at the center of this tale. The audience hears Annie before we ever see her face. Opening the film, she speaks of the musicians who can conjure spirits of the past and future. She also offers a warning—these magical souls can inadvertently attract evil. From the moment she is introduced, it’s clear she is a woman to be admired, trusted, and respected. For Elijah “Smoke” Moore, she is also a sanctuary.

Sinners: Annie

When Annie is finally revealed in all of her stunning glory, viewers find her standing in front of her modest house, surrounded by swaying trees, love, and anguish. The grave of the baby girl she and Smoke buried years before rests outside of her home, and inside, she’s surrounded by medicines, amulets and herbs. Barefoot children float in and out, paying for her services in faux cash, which she happily accepts.

Annie is a balm for Smoke, who is more stoic and discerning than his impulsive brother. The electric chemistry between the estranged couple crackles as he enters her home. Sitting on a stool, he rests (perhaps for the first time in seven years). In Annie’s presence, Smoke’s sense of relief is palpable. Her covering (in the form of a mojo bag) remains tied safely around his neck. He’s returned to her scarred but fully loved and completely whole.

Annie and Smoke’s lengthy reunion (Mosaku recalls it was a 7-page scene) is bursting with desire, eroticism, longing, wistfulness, pain, and the tender whispers of devotion. Since the origins of cinema, Black women have been shoved into boxes. Deeply melanated women with plush, curvy bodies and regal features became sexless mammies. These tropes have anchored the lie of white supremacy and even fester in the Black community itself. We are all impacted by colorism, fatphobia, and misogynoir, which continually perpetuates in present-day culture wars where Black women and men are pitted against one another.

Through Coogler’s script, which is grandly depicted in glittering 65mm and IMAX film, we see a beautiful, moisturized, intelligent, enticing woman who desires and is desired. Smoke and Annie are lustful but boast a deep reverence for one another. Without crass nudity, the audience sees her being chosen, worshiped and heard. [SPOILERS AHEAD]

Later in Sinners, Annie’s bravery and deep wealth of spiritual knowledge keep those who survive the night alive. Though gutted by his brother Stack’s transformation into a vampire, Smoke does not question her guidance. When the vampiric Stack snuffs out Annie’s life as she screams, “Not you!” Smoke honors his promise to her. Though it destroys him, he releases her soul and eventually, only after enacting his revenge, lays down his burdens to reconnect with her and their infant daughter in the afterlife.

In Annie’s final scene, she’s depicted in a balmy dream-like sequence, clothed in white and nursing a baby at her breast. This is the image Smoke sees as he crosses into the afterlife, leaving his twin in the ruthless world, choosing otherworldly freedom with the woman who has always known his soul. Black women’s bodies, sexualities and experiences are continually subjected to scrutiny and propaganda. Yet, with Annie standing at the center of Sinners, we are all reminded that Black women, especially dark skin, full-figured Black women, are and have always been every single thing. Let Mosaku’s Annie, be only the beginning of these kinds of depictions.

Written by: foxy1069

-

4942 Delmar Blvd.

St. Louis, MO. 63108

CONTACT US

- 314-782-FOXY (3699) OFC

- 314-944-1069 REQUEST LINE

- info@foxy1069.com

- ADVERTISING INQUIRIES

- scott@foxy1069.com

FOXY QR CODE